I recently got a new book called “Sailor on Snowshoes – Tracking Jack London’s Northern Trail” by Dick North. Mr. North has spent decades gathering every detail of London’s trip to Dyea and Dawson, but one incident jumped out at me that I had never heard before.

On page 81, he states that when the Nantucks spoke of “previous wrongs, it is very possible that it was the murder of the two maternal uncles of Johnny Johns they had in mind. ” Johnny Johns was the nephew of Skookum Jim Mason and Tagish Charlie. In 1982 Johnny Johns insisted that “very early in the gold rush era transgressions of the law occurred that were never reported because there were simply no law enforcement officers around. He cited the fate of his mother’s two brothers in 1896. When several white men who had set up camp on the beach at the outlet of Lake Lindeman caught an Atlin native stealing their liquor supply, they promptly shot the thief, killing him instantly. Seeing the only witnesses were two natives (who happened to be John’s mother’s brothers), they killed them as well. Word of the murders leaked out to the village people when the Native girlfriend of one of the whites told John’s mother about it.”

So, I looked through “Life Lived as a Story” by Julie Cruikshank and found the genealogy chart for Angela Sidney’s family. Johnny Johns’ mother was La.oos Tiaa, kaax’anshi or Maria Johns, married to Tagish John. Maria had two brothers who were named Tl’uku and Kult’us but there is no information on them.

Since the 1896 murder was not investigated and the murderers’ names were not recorded it would seem that in this case, they got away with murder. Then, two years later, on May 10, 1898 the Nantuck brothers take retribution for past occurrences, which presumably had to do with the white powder incident – or maybe something else.

North says that Johnny Johns’ family may have instead been referring to the 1896 murders.

An interesting thought might be that the two miners who murdered the brothers could possibly be the same two miners that the Nantucks shot in 1898.

The Nantuck brothers’ testimony seems confused, as written up in “Essays in the History of Canadian Law: British Columbia and the Yukon” by John McLaren and Hamar Foster which is viewable online. It was generally accepted that the Canadian government was trying to understand the issues involved in cases involving First Nations people and that they were beginning to rethink the previous frontier justice actions.

This week the remains of Dawson and Jim Nantuck were re-interred after they were identified in Dawson after accidentally being dug up during a construction project last summer. The Dawson cemetery is seen above.

McNeil Island

Several prisoners from Skagway were sent to McNeil Island, Washington at the turn of the century. There was an article written in the Dawson Daily News of August 14, 1905 that the Alaska Native prisoners were being kept isolated because they were all dying of consumption (tuberculosis) and were resigned to the fact that they would die in prison. The warden of the prison said that in his experience, the Alaskan natives had “a hereditary tuberculosis which was aggravated by the weather and confinement.”

They listed 12 Alaskan natives including the three which had been convicted of the Horton murders: Jim Kishtoo (Williams), Jack Klane (Mark Klanat), and Jim Hanson (Kebeth).

I believe the first two died around 1905 there and Kebeth died August 13, 1905 of consumption at age 28.

Land for the McNeil Island Cemetery was donated by island pioneers, Eric Nyberg and his wife, Martha, and the first of many burials was in October 1905. When the island’s residents were forced to leave in 1936, the cemetery was closed and all remains were exhumed and reburied in cemeteries on the mainland. So the actual resting place of these three is still unknown.

Graphie Carmack

The daughter of George Carmack and Kate Nadagaat Tlaa Kaachgaawaa Mason, Graphie was born on January 11, 1893 in Fort Selkirk, Yukon. George met Kate at Healy’s Trading Post in Dyea and they were a common-law marriage until about 1900. That year George took Kate and Graphie to Holister, California to live with his sister. He went back to Dawson where he fell for Marguerite Saftig L’Aimee a large handsome woman who ran a cigar store. Now it was said at the time that Marguerite sold more than cigars, the men loved her. George took her to Olympia Washington where they were married in October 1900. He then took Graphie from her mother and the new family moved to Seattle with Marguerite’s brother, Jacob Saftig.

Jacob, 33, fell for Graphie, 17 and she became pregnant. They married on June 30, 1910 and their first son, Ernest Charles Saftig was born three months later on October 7, 1910. Later, Graphie remarried someone named Rogers because she died as Mrs. Graphie G. Rogers on March 25, 1963 in California, either in Lodi or Los Angeles. She was 70.

I had a visitor come to my desk last summer who claimed her grandfather was G.W. Carmack, son of George Carmack and that he died in Poteau, Oklahoma but could not give me any further information, so perhaps George had other kids from either Kate or Marguerite.

There has been alot of interest in George Washington Carmack with the release of Howard Blum’s book, Floor of Heaven. It is a fun read if you haven’t read anything else on the story, but the footnotes are a little vague, in my opinion. But what do I know…seen above is a cabin with George, Kate and Graphie in happy times.

WA state records; California death index; SS death index.Canadianmysteries.ca; Johnson; Thornton; Kitty Smith oral history:Life Lived Like a story; WA 1910 census;1901 Carcross census;Polk County News, Dec 20, 1923.

Rev. Wilmot Gladstone Whitfield

In the 1902 Report of the Commission of Education Rev. Whitfield was Superintendent of the “fine Methodist Episcopal Church and parsonage in Skagway”. They said it was worth about $4500, “In spite of the business depression in Skagway the church has been able to offset removals of valuable accessions to its membership, and is harmonious and hopeful for the future.”

Rev. M.A. Sellon was another preacher who worked with him and in Klukwan to “gather the Chilkat Indians into the Church.”

Wilmot Whitfield was born on this day, March 21, 1872 in either Luana, Clayton, Iowa or the Dakotas where his father, also named Wilmot Whitfield was the presiding Methodist Episcopal pastor for the Dakota territory.

After working in Skagway, Rev. Whitfield moved to Washington where he married and then became Superintendent of Schools in Yakima Valley, Washington in 1918. He died in 1931 in Tacoma.

Above is the Presbyterian Church in Skagway which I believe is the same church they are referring to here.

History of Yakima Valley online; famsearch; WA state records

Railroad Accident

All that we know about this accident is from the Skagway Death Record which states that John Phillips, a White Pass worker was run over by the train and killed on this day, January 29, 1900. But Minter wrote that two Native American workers were killed that day and he only knew the name of Phillips.

Curiously, in February 1900 another worker, John McAllister was killed, also by falling below the wheels of the train near the White Pass summit and he is buried at Bennett Cemetery. There are also at least four other railroad workers buried at Bennett who died in the construction of the railroad between 1899 and 1900: Andrew Aidukewicz or Ajdukewicz, J. Cumberland, A. Kelly, and William Nelson. It is possible that William Nelson was the other Native American worker killed on January 29 1900 that Minter mentions since there were other Nelsons living in Skagway at the time who were Native. In all that makes at least 6 men who were killed around 1900 while working on the line, winter is a brutal time to be up at the pass.

Minter; Skagway Death Record

P.S. the three things missing from front of AB Hall in yesterday’s pic are:

1. the flagpole, 2. the hanging projecting sign, and 3. the bench.

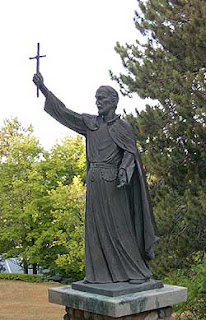

Father Pascal Tosi

Pascal Tosi was born on April 25, 1837 in Santarcangelo di Romagna, Italy. He was one of the first two Jesuits missionaries to set foot in Alaska. As the first Superior of Jesuits in Alaska (from 1886 to 1897) he is regarded as the founder and organizer of the Church in North-Alaska.

Ordained a (diocesan) priest in 1861, Tosi entered the Jesuits the following year in order to be sent to the ‘American mission’. In 1865 he arrived in the United States to serve on the Rocky Mountain Mission. For two decades he proved to be an able missionary to the Indigenous Peoples of the American Northwest.

When in 1886 Archbishop Charles John Seghers set out for northern Alaska on what was meant to be a reconnaissance expedition, he had with him as travelling companions Pascal Tosi and French Jesuit, Louis Robaut. The two were supposed to stay with the archbishop only on a temporary basis. The Jesuits had no intentions at the time of opening a new field of missionary activity in Alaska. However, the murder of Archbishop Seghers (November 1886) changed the situation, and their thinking on the matter. (see my earlier blog on Bishop Seghers)

Tosi and Robaut spent the winter of 1886-87 in Canada at the confluence of the Yukon and Stewart Rivers. When in early 1887, upon entering Alaska, they learned of the death of Archbishop Seghers, Tosi considered himself to be in charge, at least for the time being, of ecclesiastical affairs in Alaska. The following summer he made a trip to the Pacific Northwest to consult with the Superior of the Rocky Mountain Mission, Joseph M. Cataldo, who formally appointed him Superior of the Alaska Mission and entrusted him with the task of developing that mission.

In 1892, he made a trip to Rome. There Pope Leo XIII, moved by Fr. Tosi’s account of the state of the mission in Alaska, told him in their native Italian, Andate, fate voi da papa in quelle regione! (“Go and make yourself the Pope in those regions!”).

On July 27, 1894, the Holy See separated Alaska from the Diocese of Vancouver Island and made it a Prefecture Apostolic with Tosi as its Apostolic Prefect.

By 1897, Tosi was physically worn out by a tough daily life and strenuous labors in an extreme climate. He was succeeded both as Superior of the Alaska Mission and as Prefect Apostolic in March of that year by French Jesuit Jean-Baptiste René (1841-1916). From St. Michael, on September 13, 1897, Tosi sailed, reluctantly, for he hoped to stay on in northern Alaska, for what turned out to be a brief retirement in Juneau. As the ship left the harbor, a salute of four guns was ordered as a manifestation of the universal esteem in which he was held.

Tosi died in Juneau on this day, January 14, 1898 and is buried in the Evergreen Cemetery under the false name of Father Tozier.

Wikipedia; LLORENTE, S. Jesuits in Alaska, Portland, 1969;TESTORE, C.Nella terra del sole a mezzanotte. La fondazione delle missione di Alaska. P. Pasquale Tosi S.J., Venice, 1935; ZAVATTI, S., Missionario ed esploratore nell’Alaska: Padre Pasquale Tosi, S.I., Milan, 1950.; Newadvent.com

Judge Justin Woodward Harding

Justin Woodward Harding was born on December 19, 1888 and died on August 15 1972. He was a Major in World War One. He was appointed U.S. Attorney in 1921 for the First District in the Alaska Territory and later in 1927 as U.S. District Judge. And it is here that he became an Alaskan Hero. Here is the story that started on December 7, 1929 (that other infamous day in history):

“Irene Jones was a young girl, born of mixed Tlingit and white heritage. She lived in the City of Ketchikan, Alaska. In 1929 at the age of twelve, she tried to attend her local public school. She had all of the qualifications of children, who are entitled to admission and are admitted to the public school under Alaskan law. Irene was in fact a very bright and engaging student. She started attending classes at the Ketchikan school [seen above] on September 3, 1929, and was a delight to her new teacher. However, two days later she arrived at the doors of the school, to find Superintendent Anthony E. Karnes waiting for her with his arms folded and a serious expression on his face. She was sent home by Karnes on the grounds that she was of Indian descent and that she and “all of her kind should go to the Indian school”. Her parents, William Paul and Nettie Jones, made numerous pleas to the Ketchikan School Board, but to no avail. On September 10, 1929 they filed a suit on Irene’s behalf for her to be admitted to the local public school.

In 1905 Congress established a territorial school system in Alaska to provide education for “white children and children of mixed blood who lead a civilized life”. Based on this law, the legislature of Alaska established a system of free schooling for children within its jurisdiction and did not make a distinction in regard to race or color. The 1905 congressional act also mandated that education of the Eskimos and Indians in Alaska remain under the direction and control of the U.S. government, Secretary of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. The City of Ketchikan established a school system where white and mixed blood students attended schools together. However on December 7, 1928 the Ketchikan School Board adopted a resolution that modified this system. This rule said that the Ketchikan School Board would accept only those students in its locality “who are not acceptable to the United States Bureau of Education”. This meant that the School Board would no longer accept any child of Indian or Eskimo descent, including those of mixed blood.

Irene Jones’ attorney argued that the School Board violated rights provided Irene under the 14th Amendment. He presented evidence which showed that Mr. A. E. Karnes, the Superintendent of Ketchikan School District, led the effort to pass the December 7, 1928 School Board resolution to prevent children of native descent from attending Ketchikan schools. Mr. Karnes was also reported to have said to Irene: “We will get rid of all the other Native children too.” Irene’s attorney also gave other examples which showed that a school district could not override the laws of a state legislature or Congress. As a result, federal district judge, Justin W. Harding, ruled that the Ketchikan School Board had discriminated against Irene Jones and its December 7th resolution was not valid. In his final decision on November 29, 1929, Judge Harding ordered that Irene be admitted to the public school and that the School Board pay her attorney’s fees.”

And as for Karnes? Well, in 1939 he was promoted to Alaska’s Commissioner of Education, according to “A History of the Nome, Alaska Public Schools:1899 to 1958 From the Gold Rush To Statehood”, a thesis by John Poling. Karnes later retired to California and died in 1970 in Lake Elsinore.

from the court case, National Archives in Philadelphia online: Irene Jones v. R. V. Ellis et al.

George Dickinson

George Dickinson ran the Northwest Trading Post with his wife, Sarah, a Tongass Tlingit as early as 1880. In 1886 he partnered with J.J. Healy at the trading post in Dyea. He became ill and died in San Francisco on November 10, 1888.

His obituary in the Juneau City Mining Record of November 29,1888 gave his age at death as 45. Sometime later, the Healy and Wilson trading post is seen above in this Anton Vogee picture.

Neufeld:Juneau City Mining Record Nov 29 article; Daniel Lee Henry book online excerpt; San Francisco Call.

Bishop Charles John Seghers

Seghers was born on December 26 1839 in Ghent, Belgium. Left an orphan at a very early date, he was brought up by his uncles. After having studied in local institutions and in the American Seminary at Louvain, he was ordained priest on 31 May, 1863. He then left for Vancouver Island, where he was engaged missionary work among the pioneer whites and the natives. After several years of hard work establishing missions in the Northwest, the Pope appointed him Archbishop of areas in the Northwest including Alaska.

When Bishop Seghers arrived at Dyea in 1886 he was slapped in the face by the Klanot chief of the Chilkoot tribe. Undeterred, he decided to climb the Chilkoot Pass with four other men, Father Pascal Tosi, Father Aloysius Louis Robaut, the cook Antoine Provost, and a man named Frank Fuller.

When the men reached the confluence of the Yukon River and the Stewart River, Seghers decided the other two priests should spend the winter there, while he and Fuller would press on to Nulato. Father Tosi expressed concerns about this proposal, noting that Fuller had displayed signs of emotional instability. Seghers acknowledged the concern, and how the lateness of the season would likely impact his work. He gave as his reasons for going ahead anyway as his wish to fulfill a promise made to the people of Nulato to return eight years earlier. As they continued down the river, Seghers came to realize that, as traveling conditions and the boat deteriorated, Fuller’s mind did as well. On October 16, he wrote in his diary:

“Peculiar conversation with (Fuller) in which, for the third time, he gives evidence of insanity.”

On November 27, Seghers and Fuller, with two native guides they had acquired at Nuklukayet, decided to spend the night at the fish camp at what is today known as “Bishop’s Rock”. Seghers was in high spirits, laughing frequently, thinking that he would finally reach Nulato the following day. Fuller, however, remained sullen, looking suspiciously at his companions and remaining agitated throughout the night.

Between six and seven the next morning, the party arose and prepared for the final leg of their journey. As Seghers bent over to pick up his mittens, Fuller fired a single shot which killed Seghers instantly. Seghers died on this day November 28, 1886 at the age of 47.

Fuller was then arrested, taken to Sitka for trial and sent to prison for eight and a half years. When let out, in Portland, Oregon, he got into a violent quarrel with a neighbor and was himself murdered.

The remains of the bishop were ultimately transferred to Victoria and he is remembered as “the founder of the Alaska missions.”

-from AK Tribunal Papers, 1904; newadvent.org ; Gates, 1994; “Mgr Seghers,l’apotre de l’Alaska” by Maurice de Baets;

Harry Schofield

Harry, or Henry Schofield was born in 1857 in Germany and came to America in 1892. He came to Skagway from San Francisco and worked variously as a longshoreman, a seaman, and a fisherman. He got into trouble in 1900 when he sold liquor to the local Natives, and was found guilty by Judge Sehlbrede. He apparently had a liking for alcohol and on this day, November 26, 1903 died at the age of 46 here in Skagway from heart failure due to alcoholism. He is buried in the Gold Rush Cemetery.

In 2008 almost 12% of the deaths among American Indians and Alaska Natives are alcohol-related, more than three times the percentage in the general population, a federal report said. In our small community we know of one young local Alaska Native person who died from a drug and alcohol overdose a few years ago. She is buried in the Skagway “New” Cemetery on Dyea road. She is seen above at her graduation from Skagway high school in 2003.

1900 census; Thornton; Skagway death record;Newspirates.com 30 August 2008 by Jim Walrod.