Happy Birthday to little Hazel born in Skagway on October 18, 1899 to the famous White Pass & Yukon Route photographer Harry C. Barley and his wife Dora.

Barley was a late-comer to the gold rush and established an office in Skagway in 1899. He became the official photographer for WP during and after construction of the railway from Skagway, Alaska to Whitehorse, Yukon. Barley died, shortly after the Klondike Gold Rush, in San Francisco of consumption. The Yukon Archives has the most complete collection of Barley’s professional prints, including 500-700 prints of life in Skagway, WP&YR construction and various Yukon and Alaska communities.

John Robert White

An ironic story. In 1899 White Pass had a strike by its workers wanting some basic worker’s rights-a long history of issues preceded this event. (Minter, in his book The White Pass describes those.)

The leader of the strike was a young man born on October 10, 1879 in Reading, England, John Robert White. He had joined the Greek Foreign Legion in 1897 and then came to Alaska in 1899. In Skagway, the confrontation with White Pass Engineer Mike Heney and Dr. Whiting resulted in Dr. Whiting striking White on the head with a shovel. White was sent to Sitka and jailed for 6 months.

After that, White joined the military and served with the 4th Infantry in the Phillipines where he rose to the rank of Colonel. He retired from the U.S. military in 1914 and went to Europe and served for the Red Cross and the new Rockefeller Foundation (establishing medical proceedurs). He then joined the A.E.F. in WW 1.

Now here begins the ironic part:

In 1920 he joins the U.S. National Park Service. He started as ranger, then chief ranger, then Superintendent of such parks as Grand Canyon, Sequoia, and Death Valley. He then became Regional Director of two regions in the Park Service in 1940-41. White died in Napa, California in 1961 at the age of 82.

Today in Skagway the White Pass and National Park work amicably together, unaware of the history of John Robert White.

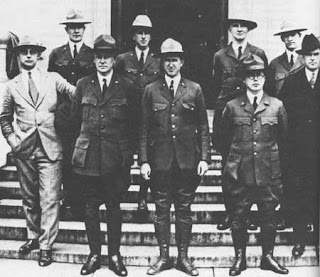

The photo above shows the Washington staff of the National Park Service in uniform in 1926. Left to right: Arno B. Cammerer, assistant director; Harry Karstens, superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park; Stephen T. Mather, director; Charles G. Thompson, superintendent of Crater Lake National Park; Horace M. Albright, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park; John R. White, superintendent of Sequoia National Park; Arthur E. Demaray, assistant director; Ernest Leavitt, assistant superintendent of Yosemite National Park; W. B. Lewis, superintendent of Yosemite National Park.

(This is from the John Robert White papers collection at the University of Oregon.)

Zachary Taylor Wood

On October 8, 1897 four RCMP officers arrived in Skagway on the S.S. Quadra. They were sent here to open an office and report on conditions. They were Inspector Zachary Taylor Wood, Captain Norwood, Major James Walsh (who had met with Sitting Bull), and Hurdman.

Inspector Wood stayed in Skagway off and on and then in May moved his office to Lake Bennett. He reported hearing gunfire on the street of Skagway one day and hitting the deck until the shots stopped. He also described a frightening time moving gold from the Yukon to Victoria, eluding the Soapy gang in Skagway by small boat.

He is a distant cousin of my husband’s family and it is inspiring to know a family member was here in the goldrush. Captain Wood died in 1915 in North Carolina while traveling, but he is buried in Caturaquil Cemetery Kingston Ontario where his family was from.

This photo shows Mrs. Z.T. Wood driving the “last spike” on the WP&YR on June 8, 1900. It says that J.T. is standing next to M.J. Heney. It also says it is in Whitehorse. Another ceremony was in Carcross on July 29, 1900 that was the last spike driven for the entire line, and was re-enacted in 2000.

“Highball Hogan” Hillery

On October 6, 1961, Albert Roy Hillery died in Juneau. He was a White Pass brakeman and conductor for many years. His descendents still live in Skagway.

In the photo above:

Part of a ten-man Rotary Fleet crew in 1946, waiting at Glacier Station for the southbound train to go by.

Standing, Mickey Mulvihill, Occie Selmer, J.L.McVey, Tad Hillary.

Seated, Howard Ballinger, Charlie Rapuzzi, Cy Richter, Howard Johnson.

White Pass murders

This day, September 30, 1915 was an unfortunate one for a White Pass & Yukon Route section crew. One of the four, Tom Bokovitch was a German prisoner of war, working his way through the war in the Yukon. With him were Henry Cook, Patrick Kinslow and George Lane.

The four men stopped for a lunch break on the track near Whitehorse when they were approached by a Russian man Alex Gagoff. Gagoff may have thought they laughed at him, in any event, he shot them all dead. He then turned himself in to the NWMP in Whitehorse. He was subsequently tried and hung on a cold (-36 below zero) day in Whitehorse on March 10, 1916.

from Law of the Yukon by Dobrowolsky

White Pass VP Hawkins

September 8, 1860 is the birthday of Erastus Corning Hawkins, the Chief Engineer of the White Pass Railroad construction and later Vice President and General Manager of the White Pass 1900-1902. He died in New York in 1912 from an operation. In the photo above you can see the four main guys responsible for building the railroad: Samuel Graves, John Hislop, E.C. Hawkins, and Michael J. Heney.

from Graves, The White Pass, and the White Pass website

Arthur Hallum

On August 29, 1898 Arthur Hallum tragically died in a railroad accident on the White Pass. He was only 39 years old, but the age of his death was strangely similar to that of his famous grandfather, Sir Arthur Henry Hallum who died in 1833.

Sir Arthur was a poet and author friend of Alfred Lord Tennyson who wrote a monumental tribute to his friend, “In Memorium” in 1850.

from: Mission Klondike by Sinclair

Father Andrew Harley Baker

On August 15, 1913 Harley Andrew Baker was born in Skagway. He was named after his uncle Harley Baker who died in Skagway in 1898 from meningitis at 3 1/2 years old and is buried in the Gold Rush Cemetery.

Harley Andrew became the first Alaska born Catholic Priest. He died in Juneau in 1965 but is buried in the Skagway Pioneer Cemetery. The Baker family stayed in Skagway until the 1930 census. Harley’s father, Elihu worked for White Pass as a brakeman.

From a website called bakercemetery.com; a letter from Francis Baker, the first Harley’s mother; census reports.

White Pass Accident 1917

On this day, August 17, 1917 a large boulder fell down the mountainside and took out an engine. The Engineer was Walter Collin McKenzie and his 25-year old son, Robert Daniel McKenzie known as “Bert”, was the fireman. They were unfortunaly both killed as the engine rolled down the mountain. No other cars or engines were affected.

In June 1908 the Baldwin Locomotive Works Co. of Philadelphia, delivered two specially designed narrow gauge steam locomotives that had been ordered by the WP&YR. Although Engine 68 was destroyed in 1917, the twin engine, No. 69 would spend the next 46 years puffing across rugged Alaskan and Canadian mountain ranges that had been conquered by the WP&YR.

WP&YR officials recognized a need for additional motive power that would primarily be used to help pull or push freight and passenger trains over the steep grades encountered between Skagway and the summit over White Pass, where the track level rises more than two feet in every 100 feet of distance. At the time of completion Engine 69, at 134,369 pounds, was one of the heaviest narrow gauge, outside-frame locomotives built by Baldwin. It was capable of tackling grades of 3.9 percent and curves and radiuses of up to 20 degrees. The tractive power of 69 was equivalent to that of many standard-gauge engines and it was well-suited to running over rails weighing 56 pounds per yard. In the course of its now-100-year history, the venerable Baldwin 2-8-0 has served in two countries, has transported thousands for either fun or profit.

from Graves, The White Pass; Skagway death records; Weather underground photo.

Black Cross Rock Incident

On August 3, 1898, while building the White Pass & Yukon Route Railroad, Michael J. Heney, the company foreman and chief engineer was supervising some blasting at a place called Black Rock which is about 13 miles up the track from Skagway.

As the explosion went off, a huge slab of rock slid down over two men. At first, rumors flew that there were more casualties, but in the end it was confirmed that there were just two.

As the explosion went off, a huge slab of rock slid down over two men. At first, rumors flew that there were more casualties, but in the end it was confirmed that there were just two.

The company decided that there could be no better memorial to these two men than the rock and so a small memorial was placed there.

Over the years the names of Al Jeneux and Maurice Dunn have been given for the two men, although in all the research, I have yet to find any historical reference to confirm those names.